‘Idiot,’ ‘Yahoo,’ ‘Original Gorilla’: How Lincoln Was Dissed in His Day

The difficulty of recognizing excellence in its own time

By nearly any measure—personal, political, even literary—Abraham Lincoln set a standard of success that few in history can match. But how many of his contemporaries noticed?

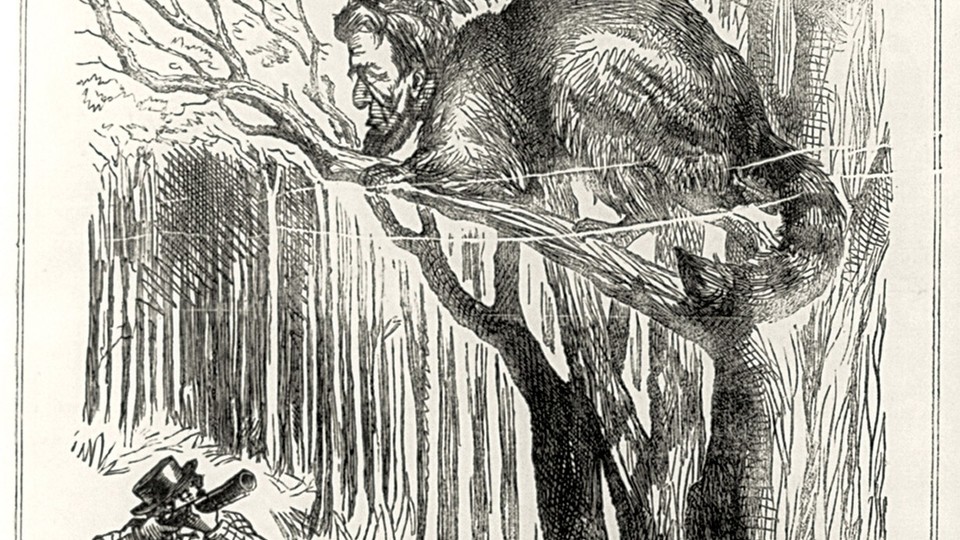

Sure, we revere Lincoln today, but in his lifetime the bile poured on him from every quarter makes today’s Internet vitriol seem dainty. His ancestry was routinely impugned, his lack of formal learning ridiculed, his appearance maligned, and his morality assailed. We take for granted, of course, the scornful outpouring from the Confederate states; no action Lincoln took short of capitulation would ever have quieted his Southern critics. But the vituperation wasn’t limited to enemies of the Union. The North was ever at his heels. No matter what Lincoln did, it was never enough for one political faction, and too much for another. Yes, his sure-footed leadership during this country’s most-difficult days was accompanied by a fair amount of praise, but also by a steady stream of abuse—in editorials, speeches, journals, and private letters—from those on his own side, those dedicated to the very causes he so ably championed. George Templeton Strong, a prominent New York lawyer and diarist, wrote that Lincoln was “a barbarian, Scythian, yahoo, or gorilla.” Henry Ward Beecher, the Connecticut-born preacher and abolitionist, often ridiculed Lincoln in his newspaper, The Independent (New York), rebuking him for his lack of refinement and calling him “an unshapely man.” Other Northern newspapers openly called for his assassination long before John Wilkes Booth pulled the trigger. He was called a coward, “an idiot,” and “the original gorilla” by none other than the commanding general of his armies, George McClellan.

One of Lincoln’s lasting achievements was ending American slavery. Yet Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the famous abolitionist, called Lincoln “Dishonest Abe” in a letter she wrote to Wendell Phillips in 1864, a year after Lincoln had freed the slaves in rebel states and only months before he would engineer the Thirteenth Amendment. She bemoaned the “incapacity and rottenness” of his administration to Susan B. Anthony, worked to deny him renomination, and swore to Phillips that if he “is reelected I shall immediately leave the country for the Fijee Islands.” Stanton eventually had a change of heart and lamented her efforts against Lincoln, but not all prominent abolitionists did, even after his victory over slavery was complete, even after he was killed. In the days after Lincoln’s assassination, William Lloyd Garrison Jr. called the murder “providential” because it meant Vice President Andrew Johnson would assume leadership.

Lincoln masterfully led the North through the Civil War. He held firm in his refusal to acknowledge secession, maneuvered Confederate President Jefferson Davis into starting the war, played a delicate political game to keep border states from joining the rebellion, and drew up a grand military strategy that, once he found the right generals, won the war. Yet he was denounced for his leadership throughout. In a monumental and meticulous two-volume study of the 16th president, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008), Michael Burlingame, the professor of Lincoln studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield, presents Lincoln’s actions and speeches not as they have come to be remembered, through the fine lens of our gratitude and admiration, but as they were received in his day. (All of the examples in this essay are drawn from Burlingame’s book, which should be required reading for anyone seriously interested in Lincoln.) Early in the war, after a series of setbacks for Union troops and the mulish inaction of General McClellan, members of Lincoln’s own Republican party reviled him as, in the words of Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, “timid vacillating & inefficient.” A Republican newspaper editor in Wisconsin wrote, “The President and the Cabinet,—as a whole,—are not equal to the occasion.” The Ohio Republican William M. Dickson wrote in 1861 that Lincoln “is universally an admitted failure, has no will, no courage, no executive capacity … and his spirit necessarily infuses itself downwards through all departments.”

Charles Sumner, a Republican senator from Massachusetts, to whom Lincoln often turned for advice, opposed the president’s renomination in 1864: “There is a strong feeling among those who have seen Mr. Lincoln, in the way of business, that he lacks practical talent for his important place. It is thought that there should be more readiness, and also more capacity, for government.” William P. Fessenden, the Maine Republican, called Lincoln “weak as water.”

For anyone who struggles to do well; to be honest, wise, eloquent, and kind; to be dignified without being aloof; to be humble without being a pushover, who affords a better example than Lincoln? And yet, as he saw how his efforts were received, how could even he not have despaired?

His wife said that the constant attacks caused him “great pain.” At times, after reading salvos like Henry Ward Beecher’s, Lincoln reportedly would exclaim, “I would rather be dead than, as President, thus abused in the house of my friends.” Lincoln would often respond to the flood of nay-saying with a weary wave of his hand and say, “Let us speak no more of these things.”

Democracy is rowdy, and political abuse its currency, so perhaps the invective aimed at Lincoln was to be expected. But how do we explain the scorn for Lincoln’s prose?

No American president has uttered more immortal words than he did. We are moved by the power and lyricism of his speeches a century and a half later—not just by their hard, clear reasoning, but by their beauty. It is hard to imagine anyone hearing without admiration, for instance, this sublime passage from the first inaugural address:

I am loth to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Yet this speech was characterized by an editorial writer in the Jersey City American Standard as “involved, coarse, colloquial, devoid of ease and grace, and bristling with obscurities and outrages against the simplest rules of syntax.”

As for the Gettysburg Address—one of the most powerful speeches in human history, one that many American schoolchildren can recite by heart (Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth …) and a statement of national purpose that for some rivals the Declaration of Independence—a Pennsylvania newspaper reported, “We pass over the silly remarks of the President. For the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them, and they shall be no more repeated or thought of.” A London Times correspondent wrote, “Anything more dull and commonplace it wouldn’t be easy to produce.”

And the second inaugural address (With malice toward none, with charity for all …), the third major pillar in Lincoln’s now undisputed reputation for eloquence, etched in limestone on the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.? A. B. Bradford, a Pennsylvania pastor and a member of one of the oldest European families in America, wrote that it was “one of the most awkwardly expressed documents I ever read … When he knew it would be read by millions all over the world, why under the heavens did he not make it a little more creditable to American scholarship?” The New York Herald described it as “a little speech of ‘glittering generalities’ used only to fill in the program.” The Chicago Times, a powerful voice in Lincoln’s home state: “We did not conceive it possible that even Mr. Lincoln could produce a paper so slip-shod, so loose-jointed, so puerile, not alone in literary construction, but in its ideas, its sentiments, its grasp.” Poor Lincoln. By all accounts he appears to have been the gentlest and most honorable of husbands and fathers, and yet he found little solace even at home. Burlingame records the constant duplicity and groundless suspicion, the nagging criticism and jealous rants of Mary Todd Lincoln, who, on a steamboat home after her husband’s triumphant entry into a fallen Richmond, reportedly flew into such a rage that she slapped him in the face.

“It is surprising how widespread [the criticism] was,” Burlingame told me recently. “And also how thin-skinned he could be. But that was the nature of partisanship in those days; you never could say a kind word about your opponent.”

As if things have changed.

Of course, Lincoln was elected twice to the presidency, and was revered by millions. History records more grief and mourning upon his death than for any other American president. But the past gets simplified in our memory, in our textbooks, and in our popular culture. Lincoln’s excellence has been distilled from the rough-and-tumble of his times. We best remember the most generous of his contemporaries’ assessments, whether the magnanimous letter sent by his fellow speaker on the stage at Gettysburg, Edward Everett, who wrote to him, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes”; or Edwin Stanton’s “Now he belongs to the ages,” at the moment of his death; or Frederick Douglass’s moving tribute in 1876 to “a great and good man.”

This process of distillation obscures how Lincoln was perceived in his own time, and, by comparison, it diminishes our own age. Where is the political giant of our era? Where is the timeless oratory? Where is the bold resolve, the moral courage, the vision?

Imagine all those critical voices from the 19th century as talking heads on cable television. Imagine the snap judgments, the slurs and put-downs that beset Lincoln magnified a million times over on social media. How many of us, in that din, would hear him clearly? His story illustrates that even greatness—let alone humbler qualities like skill, decency, good judgment, and courage—rarely goes unpunished.