It’s amazing how much personal info gets exchanged when you’re about to go running for the first time with a stranger. Of course, there are the basics: weekly mileage, average pace, is either one of you currently training for a race? How do you feel about hills? Trails? Watches? What's your best time of day? And that's just the beginning, at least for me. Or perhaps I'm just an extreme case--the definition of oversharer--but by the time I finally go running with Jamie Quatro, she knows not only about my recent breakup and my mom's cancer, she also knows that I'm in pain. I don't mean just the emotional variety. I'm talking plantar fasciitis: a burning in my right heel that feels like it's never going to go away.

I reassure myself that it's only fair for her to know this stuff; after all, I've read her book. Twice. In a way, I already know all about her. More important, she's a mom herself. I can tell already that she gets me.

"I had a pretty bad case of plantar last year," Quatro admits, never breaking eye contact even while locating the "Apple+S" with thumb and forefinger and closing up her laptop. I've caught her at the end of her morning writing session at her favorite coffee shop in Chattanooga. "What kind of insoles are you using?"

"Insoles?" I say, as if she's suggesting amputation.

"Powersteps!" she says, almost jumping out of her chair with excitement. "Let's go get you some. Maybe this trip is gonna be about healing."

* * *

Everyone talks about "escaping" into a book, but even as a kid, the escape was never what I looked for. The characters might not resemble me in the slightest, the setting might be totally unfamiliar, but I've always hoped to find some new piece of myself--a string of words capturing my own feelings exactly. My favorite kind of reading is like looking through a window at a rainstorm: You're staying dry, but once in a while, the light might allow you to see your own reflection out in it.

Last winter, when Mom was well, when I could do such things as read entire books in single sittings, I burned through Jamie Quatro's I Want to Show You More. There is such a scarcity of good literature about running (it's a struggle to name one running-related novel or short story not by Alan Sillitoe or John L. Parker, Jr.) that Quatro's debut short-story collection hit me even harder than it hit the critics. And it hit the critics pretty hard.

Quatro, age 43, has had the kind of year most writers will never have. I Want to Show You More wowed the tastemakers at The New Yorker and The New York Times, and came out in paperback earlier this year. "There's so much in these stories that's shocking," wrote Dwight Garner in The New York Times. "Yet there's so much solace." Her work has most often been compared to one of the giants of the form: Flannery O'Connor. This comparison holds water--both writers are concerned with matters of faith, and unafraid to peel away the darkest aspects of human behavior. The rare instances of redemption feel hard-won, brutally authentic. And the passages about running? In Quatro's hands, our sport is both transcendent and terrifying.

I've arranged to spend a couple of days visiting Quatro on Lookout Mountain, Georgia, where she lives with her husband, Scott, and four kids. She's taking me running on her usual, everyday route. The idea is to talk about where her stories come from. Running as part of the creative process. A profile of one of the most literary runners in North America: That is the essay my editor is expecting. But all I really want to talk about is how much I already miss Mom.

We drive through downtown Chattanooga, cross over the Tennessee River, and park behind Fast Break Athletics, the local running store. As soon as we're inside, I realize that Quatro is multitasking: She's picking up a new pair of shoes while I try out the insoles. She runs 30 to 35 miles a week, about twice my average, and clearly shops here a lot. The first employee we encounter, Michael Green, knows exactly her model and size. I'm too distracted by a framed article from a 2002 issue of this magazine to jump in on the conversation.

"Now I'm hoping you'll be able to take care of Michael," Quatro says to Green, and goes on to explain my problem.

As Green pulls out my beaten blue insoles and slides the bright new orange ones into my aging running shoes, I try to reconcile the fierce, often disturbing intelligence behind I Want to Show You More with the friendly woman worrying about my foot. It's hard to imagine her at work. But I know that running is a big part of her process. Before the advent of smartphones, Quatro sometimes used to stop on her long runs, pick up a stick, and scratch a word or two into her arm to remind her what to do with a story when she got back home. Her best-known story, "Ladies and Gentlemen of the Pavement," a twisted tale about a futuristic marathon in which the already sadistic elements of running 26.2 turn totally unforgettable (in Quatro's race, the runners must carry statues--the majority grotesque, a select few breathtakingly beautiful), came out of the frustration of getting a stress fracture while training for her first marathon.

"It was my first stress fracture," she explains, "in my femur. I ended up running the half, and after a second stress fracture, I decided I would have to let the marathon dream die. So if you want to go there, there's a literal and personal interpretation of the ending of 'Ladies and Gentlemen': Jamie, if you push to 26.2, you will die. Your femur will snap. And yet I knew it was ridiculous to think I couldn't be a 'real' runner unless I'd done a marathon.

"When people say the short story is practice for the novel," she continues, "or that you're not a 'great' writer unless you've written a novel, I always think: That's like saying the half marathon is practice for the marathon, or that the half is easier to run than the full, or that you're not a 'great' runner unless you've done a marathon. Each distance--each literary form--is its own thing, with its own challenges and heartbreaks."

I'm nodding enthusiastically. As a failed novelist turned essayist (and as a runner who has yet to so much as attempt a half marathon), I find what she's saying totally life-affirming.

"Running isn't about what distances you've raced," she reminds me. "Or even if you've done a race. So there might be a bit of that type of thinking in 'Ladies and Gentlemen,' a bit of a thumb-to-the-nose to folks who say you have to run a marathon or write a novel to be legit. Not enough of us are talking about what a holistic sport it is, or should be. It's about staying fit and pushing yourself to achieve and surpass goals, sure; but it's also about personal and spiritual growth, creativity, mental clarity, and emotional stability. I find these things in running. Even if I can only do a couple miles at a 10-minute pace."

Of course, anyone who runs as much as Quatro runs has a great deal of self-discipline: at least twice as much as I do, if these things can be measured (and I kind of think they can). And so it's with a sense of relief that I hear her confess about wasting so much time on Facebook that she'll often ask Scott to change her password and withhold it until she's worked out the crux of a story.

"That's where running is so unique," she says. When she's done for the day, or when she just needs a break, she'll put on her shoes, and within a mile or two be totally absorbed, just relaxing into her run, when suddenly she'll realize that what she's actually doing is figuring things out, thinking back over what she worked on that morning. "Most of my best ideas come away from the computer," she explains. "That kind of reflection just isn't possible online."

Green hands me my shoes, and I slip my feet back into them. I don't know how else to say it. They feel... new.

* * *

On our way up Lookout Mountain, the fabric of Quatro's book begins to unfold before us. "So now we're on 58 South," she tells me, pointing at the sign, "the road where that first line comes from." It's almost like she's showing me a note on a napkin, that first flash of a story.

I know exactly which sentence she's talking about. "Dying is like driving south up a mountain," a young mother tells her husband at the beginning of "Georgia the Whole Time." Readers know already from an earlier story in the collection that this character will lose her fight with cancer, and so the unconventional chronology stirs an almost unbearable sadness into every little corner of the latter story. After rereading "Georgia" on the plane in from Portland, Oregon, yesterday, I pressed my forehead to the plexiglass and waited for my shoulders to stop shaking.

Lookout Mountain is one of those weirdo geological marvels that, like Herman Melville's Mount Greylock (allegedly the inspiration for Moby Dick), seem designed to inspire great American literature. Seventy-five miles long, rising out of the lowlands of Georgia and Alabama, its two brows meet at an abrupt, towering end above the city of Chattanooga. From below, the massive, cliff-studded face resembles a turn-of-another-century steamship. How appropriate, that the mountain seems forever poised to churn defiantly northward: One of the epic stands of the Confederacy ended on a meadow just below the summit in November 1863. By the end of "Georgia the Whole Time," Quatro's heroine has decided for the remainder of her life to avoid 58 South, the road we're on, and take the roundabout way up, where "there are no signs about battles."

Jamie and Scott are relatively new to the South, having moved from Arizona only eight years ago. Until arriving here, they'd been bounced around the country, chasing Ph.D.s (Jamie has literary degrees from Bennington, William & Mary, and Pepperdine) and teaching jobs (Scott is now a professor at a local college) while somehow managing to start their family. But no matter where they've lived, one constant for Jamie has been running: entering the landscape every day. And so, perhaps unsurprisingly, the South is already all over her writing.

Despite the abundant sunshine, it's cold in Tennessee. Or are we in Georgia yet? Once we reach the plateau atop Lookout Mountain, the cliffs give way to rolling green lawns and windy roads: the pre–trip mall suburban dream. The town of Lookout Mountain straddles the border between the two states, an oddity that Quatro explores throughout her book. In "Georgia the Whole Time," the difference between the states is felt most significantly by the difference in leash laws: Georgian dogs are allowed to wander. "Every time I hear that another dog has been hit by a car," Quatro writes, "I know which side it lived on."

Now, she confirms that the law is a real thing. "Sometimes when I'm out running," she says, "a Georgian dog will decide to tag along. It makes me nervous. There's not much I can do except avoid the houses where the most curious dogs live--and run on the Tennessee side."

Something about how the story and the road and my own circumstances have aligned makes me feel comfortable asking Quatro if she's lost her own mother. "I've lost friends," she says, "but my mom is doing well."

As we're nearing her house, I ask if we'll pass by the four-way intersection at the border between Georgia and Tennessee. "Michael," she says, "there is no intersection at the border. It's fiction. A couple folks up here have given me grief for getting the facts wrong. But that's one of my favorite parts of fiction. Moving real things around."

Two days ago, my mom was playing around with her oxygen. When she retucked the tubes behind her ears and asked me how they looked, I was briefly reminded of how she used to put on a pair of sunglasses. "What's this lady's name again?" she asked me.

"Jamie."

"Okay," she said, "I promise not to die while you're in Georgia interviewing Jamie."

I made an exaggerated inhalation. Mom closed her mouth and imitated me. She'd always been a mouth breather, but finally, at 70, she was learning how to breathe through her nose. Otherwise the oxygen would really have been sort of pointless. She and I were both chronically stuffed up; if not for the thrum and gurgle of the oxygen machine, the rest of the family would have been able to hear us breathing from out where they were waiting in the living room.

"Is that any better?" she asked.

"Closer," I said, sucking air back in through my nostrils. "But once isn't enough. You have to keep doing it."

"I was talking about your trip. Do you feel any better about going after hearing me say that?"

"Sure," I said, as if she were offering to pick me up from the airport.

"And I promise not to call up Jamie and say," here she made her voice sound as tiny and ridiculous as possible, "'Jamie, put Michael on the phone, this is his mother. I'm dying.'"

We both laughed.

"Go," she said. "Go. I'll be here when you get back."

* * *

We’re walking down Quatro's driveway, shivering in the cold sunlight, our sleeves pulled over our hands. We're not running yet, but we're finally really talking about it.

"It was the thing that saved me after my fourth child was born," Quatro confesses.

"We had four kids in five years, all by the time I was 30, and I had postpartum depression after number four."

I've just met two of the four Quatro kids, not to mention their dog, but she has asked me to respect the privacy of her family, so I'm going to describe the kids as "teenage" and the dog as "doglike" and leave it at that. Considering that many of the stories in her book feature a mother-of-four involved in a highly charged, long-distance affair, the maternal instinct to protect her brood from unsubtle journalism confusing fiction with fact seems not only wise, but refreshing in this don't-forget-to-tag-me-on-Facebook age.

"The doctor told me I could treat it with Lexapro or vigorous exercise," she continues. "Easy choice."

"Wow."

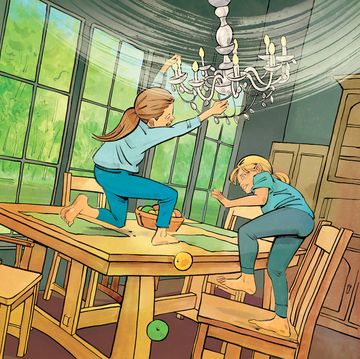

"It's amazing," she says, "the things that can happen on a run. Especially when I go straight from writing to running, all these solutions will occur to me." She goes on to admit that sometimes when she gets home from a run, she'll be in such a hurry to get her ideas down that she often neglects stretching. "The kids will be like, 'Mom!' and I'm like, 'Out of my way, where's my laptop!' But other times I'll come home to them and think, Ahhhh, it's so nice to not be writing right now."

"Is it easier to run than to write?"

She pauses. "Writing is hard," she says. "Much harder than running. Most days I'd rather run than write."

"I'm so glad to hear you say that," I admit. The truth is, I'm never more eager to lace up my shoes than when my own writing is going poorly. We joke about how running has become our drug of choice.

Quatro goes on to tell me that she does not buy into the myth of the hard-drinking writer. " 'Keep a clean life so you can be messy on the page,' " she says. "I believe in that motto. That said, my tolerance has gone up. These days it takes a bit longer for the endorphins to hit."

We're standing in the middle of the road, waiting for one of us to make a move. I know from all the e-mailing leading up to this that we're going to run a tiny bit slower than I'm used to running, and that right around mile seven she's going to start feeling really awesome and I'm going to start feeling really tired. She warns me that after hurting herself a couple times on Lookout's uneven terrain, she has taken to walking some of the steeper downhills in the name of staying healthy. "The injuries have really forced me to reevaluate," she says. "The first time I ran after the stress fracture--and it was only for a mile or so--I almost wept with joy."

Silenced by that thought, I bounce on my toes, and suddenly we're in motion. There's that awkward moment of trying to match a new running buddy's pace, while wondering if the new running buddy might be attempting, perhaps subconsciously, to bridge the gap. Which would mean that this pace we're running isn't actually either one of our paces, but rather a crude kind of guess. But it only takes a couple rounds of "Is this pace okay?" for it to begin feeling truly okay. Only now do I realize to what degree I've been craving this all day.

While attempting to ignore the usual first-mile burning in my heel, I wonder, not for the first time, if maybe I've been pushing it too much. Compared to other people, I may not run an awful lot, but it sure feels like a lot to me. Especially this past month: Most days it's the only thing I feel justified leaving the house for. I've been measuring my breaks in terms of miles. Two days ago I took an eight-mile break on Wildwood Trail. But this--this is a 2,000-mile break. Sometime today, like possibly even right now, we'll be getting the results from last week's biopsy. I can't quite believe that the rest of my family might be sitting in the oncologist's office right now; that I'm not with them, clinging to the shreds of our collective hope. What am I doing? Why am I running?

The story that brought me here comes about two-thirds of the way through the collection. "Sinkhole" is set at a Bible-study summer camp, where a 15-year-old running prodigy is battling what appear to be pretty much the most frightening panic attacks ever. Whenever he feels anyone getting too close, this spot in the middle of his chest, "like a scar that cannot be touched by anyone or anything," begins to open. This is his Sinkhole, and if he doesn't lie down and do this thing he calls "the Gesture," which basically involves massaging the air right in front of his Sinkhole, slowly closing it up, the Sinkhole will spiral all the way to his heart and kill him.

And yet, when he sets out on the trails, he actually tries to bring on the Sinkhole, as if it's some kind of transcendent runner's high:

These early minutes are the gray space, the bland miles I have to run through before the prickling starts and the God rhythms pulse in my heart and I have to trick myself into not listening.

My therapist says when this happens, it's the first hit of endorphins. It's not God, it's biology, he says.

My therapist is not a runner.

The story's ending, like Quatro's family, is indescribable. "I wanted to write about an exorcism in which neither character realized what was happening to the other," she tells me now. "And turn awkward teenage sex on its head."

"It's so close to being a happy ending," I say. "Which is why that gap between them is so sad."

Somehow the story weaves together all these seemingly unrelated threads--religion, illness, adolescence, and, yes, sex--and ends up capturing the desperate interior life of a 15-year-old as well as anything I've ever read. In "Sinkhole," Quatro gives us life as it is most intensely lived. On a purely technical level, the story floors me, but the thing that got me on the plane to Tennessee was this curiosity, this need to know: How does this lady know so much, not just about me, but about all of us?

I’m filling the cold air with questions, mostly about her "process" and "craft," which she graciously answers. This loop, she explains, she usually does solo. A number of stories she's currently working on are set at various landmarks along this route. I think about my stomping grounds back in Oregon, how bored I get of the usual twists and turns. How blind I have been to the possibilities in my own landscape. We end up talking about the difference between "looking" and "seeing," a.k.a. the difference between art and everything else.

But I can't shake the notion that there's something I'm not asking. Or something she's not saying. Eventually, around the three-mile point, when running begins to feel like the most natural thing we could be doing, the questions taper off. We're gliding along a quiet, curvy road toward Point Park, where the eastern brow of Lookout Mountain will meet its western brow--the front of the ship, in other words. Legend has it you can see seven states from the top of Lookout, and the occasional glimpse reveals what, for all I know, might be the entire brush stroke of Tennessee.

As we pass a sign for the Lookout Mountain Incline Railway, the country's steepest passenger railway, Quatro ducks inside the tiny terminal. I chase her through the lobby, suddenly self-conscious of my running tights, and out to the deck, where we peer over the railing at the track plummeting down toward Chattanooga like a ski jump with no jump. A tourist trap, I assume, until Quatro explains that the doctors and nurses who commute down to the city take the Incline when snow or ice makes the drive too treacherous. I would scoff at this suggestion of winter in the South except that when I arrived yesterday, despite the flowering dogwoods and cherry blossoms exploding outside my rental car windshield, I was met by snow flurries.

"Snow out of season," Quatro says slowly. "That might be a good place to begin."

It takes me a second to realize that she's talking about my mom, about the cancer, about my own story. "I keep thinking that maybe you should be the one writing this essay," I say.

"Actually," she says, laughing, "I used to dream of writing for Runner's World. I'd look at the Rave Run, at the picture of some admittedly picturesque place, and think, But mine are so much better." She pulls back from the railing and we head back toward the lobby. Just before reentering the lobby, she freezes midstride, glancing back at me. "Many years ago," she confesses, "when we were living in Iowa and I was in the midst of having all these children, I might have even sent in an essay to the magazine."

"What?" I sputter, delighted by this image: the twenty-something Quatro, unpublished, searching, a decade before the stories that would change her life.

"It was about this bizarre stop sign in the middle of a cornfield. If I can find it, I'll send it to you."

"Did you ever hear back?"

She smiles. "Well, you're here now, aren't you?"

* * *

Hi Michael,

I hope you made it home okay. How is your mom?

As promised, here is that excerpt from my old journal, as well as some sketched notes I found. Turns out I even sent this to RW! These are undated, but I'm guessing it was Feb 2000. Three kids, at that point, ages 4, 2.5, and 16 months.

Oh, and that Gilbert poem is called The Lost Hotels of Paris, about Ginsberg's despair of never getting it quite right. I think of it, often, whenever I'm close to finishing something and I realize I have, once again, failed my original vision. And remember Beckett's injunction to fail again, fail better...

JQ

Ideas for reflections on running, possibly for RW?

1. Past the last post (thesis/stop sign connection).

2. The space between the run & going back inside. The space between the heart pounding, sweaty thoughts flowing middle of run and the chaos waiting inside the house, the kids. But the middle space between these--the pause after the run, before the run in-side--I drink this like water. Gray snow beneath pallid skies, colorless, flat; our clothesline frozen stiff, weight of icicles pulling it down. A flock of crows twisting overhead, restless to find a tree. They chatter, unsettled, then beat off again. Endless quest for rest. And I've found mine, here, in this space--the just after and just before.

Past the Last Post

I run on a fitness trail. It begins at a busy corner near the elementary school, follows the blacktop for a mile, then twists southward into the cornfields and ends at a swimming hole and run-down campground beside the golf course, three miles outside of town. This is where I turn around.

It's an unimpressive stretch of nothingness. In the summer, head-high corn flanking the path blocks the view. I feel like I'm running through a tunnel. After the harvest, the sense of raw space is dizzying. There is nothing to look at, in any season, nothing to break up the monotony of the six-mile round trip. The first time I ran with a local, the first winter after we moved here, she told me the exact number of telephone poles between the school and campground, explaining how to calculate mileage in telephone poles.

I must have looked as baffled as I felt, because she said, sheepishly, "You'll get used to it."

"Used to counting the poles?" I asked.

"Used to having nothing to look at but the poles," she said.

She was right--almost. There is something else, at the turnaround. It's random and inexplicable, there's no reason for it to be there, and for that reason alone, I look forward to reaching it each time I run.

It's a small post, about four feet high, with a full-size stop sign at the top. It is, especially in the shades-of-gray months, a splash of color, and a reminder that, if I can just push past it, keep going—

* * *

It’s impossible to say when the healing begins. Is it with that first cushy step back in Fast Break, when, instead of the usual stretching and tearing, my plantar fascia finds itself dozing off in its new cradle?

Is it during my final strides with Quatro, when, instead of the planned 11 miles, we decide on 7.5 and a side trip to see Rock City, the rock garden to end all rock gardens, all labyrinthine paths and cliff edges and blacklit fairytale rooms?

Is that where the healing begins, there in the cold sunlight amid a gaggle of schoolchildren, with Quatro telling me how more than 80 years ago, Frieda Carter first traced the 4,100-foot walking trail through Rock City Gardens, unwinding a ball of string, unaware that her efforts would result in one of the legendary attractions of the American South?

Or is it simply the fact that I keep going, taking steps over the next two weeks, as Mom's cancer gets a name and continues racing through her organs and bones, and "six months to a year" becomes "one to two months" becomes "any day now" and the only thing I leave the house for is my daily break on Wildwood Trail?

The day before she dies, when the endorphins hit, they bring with them a storm of tears and shivers.

My Sinkhole, I can't help but think.

I try to tell myself it's okay if she's gone when I get back, if I've said goodbye for the last time. But underneath my sweat is a terrible fury. I'm in the best shape I've been in since the '90s. Why can't I give some of this to her?

The inherent selfishness in what I'm doing brings me to a stop in the middle of the trail. I yank off my shirt and feel each heartbeat shake my entire body. What right do I have to go for a run at a time like this? I can feel my shoulders bending under the weight of this question, a series of cramps stirring in my gut. Insoles are one thing, but what I really need are new thoughts. And for the thousandth time this month, it's Jamie Quatro's words I'm reaching for. This time, however, I'm grabbing at ones she never meant to get published.

The space between the run and going back inside... The just after and just before.

Fourteen years ago, Quatro was running from--and toward--something very different. But family is family. Chaos is chaos. And without these breaks, these splashes of color, we might not know how to find meaning in all that noise.

I roll up my shirt and tuck it into my shorts. I don't bother restarting my watch. It doesn't really matter how fast I'm going. I'm just a kid running home to his mom one final time. When I reach the patio, I yank off my shoes and socks. Standing there, gulping in the almost unbearably sweet spring air, I let myself not know for one more moment. And then I burst inside, and kneel beside her, and hide my muddy knees, and hold her hand, and try to stop time.